Celebrating Native American Heritage

Season 28 Episode 23 | 52m 26sVideo has Closed Captions

Celebrate incredible art and artifacts from Indigenous creators and history makers.

Celebrate incredible art and artifacts from Indigenous creators and history makers. Was a Sioux beaded vest, ca. 1876, a Ruth Muskrat Bronson archive, or a Carrie Bethel basket the top $75,000 to $150,000 find?

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Funding for ANTIQUES ROADSHOW is provided by Ancestry and American Cruise Lines. Additional funding is provided by public television viewers.

Celebrating Native American Heritage

Season 28 Episode 23 | 52m 26sVideo has Closed Captions

Celebrate incredible art and artifacts from Indigenous creators and history makers. Was a Sioux beaded vest, ca. 1876, a Ruth Muskrat Bronson archive, or a Carrie Bethel basket the top $75,000 to $150,000 find?

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Antiques Roadshow

Antiques Roadshow is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

ANTIQUES ROADSHOW's 2026 Production Tour

Enter now for a chance to win a pair of free tickets to one of the three stops on ANTIQUES ROADSHOW's 2026 Tour. Sweepstakes entry deadline is April 6.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪ ♪ CORAL PEÑA: Incredible art and artifacts from Indigenous creators and history makers are in the spotlight.

To read through that speech, it gives me goosebumps.

I just... (exclaims): I can't breathe.

PEÑA: It's "Antiques Roadshow: Celebrating Native American Heritage."

♪ ♪ PEÑA: In this special hour of "Roadshow," we've gathered some of the most compelling Native American objects ever to be brought before our cameras.

Items from Indigenous icons like Jim Thorpe... You brought us this great letter dated July 20, 1933, from one of the greatest athletes of all time.

PEÑA: ...Maria Martinez...

Her pottery is very highly sought-after today and very collectible.

PEÑA: ...and Charles Loloma are here.

His influence and his impact on jewelry altogether has just been unprecedented.

PEÑA: As well as pieces by unknown artists and makers that are cherished today.

It just has all the elements in it that clearly indicate Native American-made.

PEÑA: Each of these treasures speaks to the rich and diverse traditions, histories, and cultures of Native Americans.

Like this family heirloom from the Great Plains.

It's always been-- I consider it a family piece.

It came down from my grandfather through my father to me.

My grandfather was Chippewa, from the White Earth Reservation in Minnesota, and then he married a Ponca from out in Niobrara, Nebraska.

That's where my father was born, I'm assuming on the reservation there.

But my father is also registered Chippewa, so...

I see.

Clearly, we have a, a vest.

It's an extraordinary example.

It's, it's neither Chippewa nor Ponca, it's made by the Sioux.

Okay.

This was made o, on the Great Plains, Central to Northern Plains, maybe in Minnesota.

Okay.

And, and they're somewhat beyond Minnesota, into the Dakotas.

It's glass beads, and they were traded to the North American Indians, perhaps in exchange for animal pelts-- beaver, deer, buffalo, that sort of thing.

Very good.

It's made in, uh, completely traditional fashion.

It, the beadwork is on brain-tanned animal hide.

The fringe is very traditional, and it would move with the wearer.

The designs are ancient designs, and these are traditional geometric designs that would associate the imagery with the powers of both the upper and the lower world.

Along the side here and coming down here, you have zigzag elements.

They may reflect lightning.

But really, there are three things going on.

The garment is made to keep somebody warm.

It would additionally identify your tribal affiliation.

Anybody on the Great Plains that would see this vest would immediately know this is the, wearer is associated with the Sioux people.

Okay.

These are very distinctive Sioux designs.

And in addition, these images protect the owner-- they're empowerment.

Okay.

So you would have the assistance of the powers of the upper world, the assistance, perhaps, of the powers of the lower world, as well.

The beads, by the way, are attached to the hide with sinew.

Oftentimes, when you see an hourglass figure...

Very good, yeah.

...in the abstract, it may represent a thunderbird.

If we turn this, the poles of the flags create an hourglass figure.

Right.

And that, in addition, may be seen as a thunderbird image.

We have traditional elements here.

Mm-hmm, okay.

But we have two amazing American flags, each with 13 stars.

So this is probably a replication of an existing flag that this Sioux woman saw.

Oh, yeah.

She wanted to put it on the vest.

It further empowers the owner i, in a certain sort of way.

Mm-hmm.

This doesn't necessarily reflect patriotism as much as respect for this new power that's come into their land.

One way we might be able to date this vest, is may be exactly 1876, a centennial year.

Okay.

And Native Americans created many, many objects depicting the American flag in 1876.

Okay.

If it's not 1876, I would guarantee you it's within five or ten years of that date.

The value, on a retail basis, without the American flags, I think, would be in the neighborhood of $3,500.

Okay.

The fact that it has these two figural elements, the, the flags, I think doubles the value of this vest.

Okay.

I think, on a retail basis, we're now looking at $7,500.

Okay.

Should you wish to insure this...

Okay.

...I think you could insure this vest at around $10,000.

Okay.

It's, it's spectacular.

Very good.

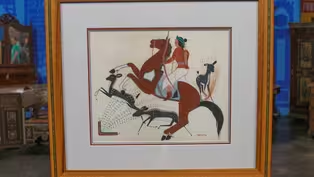

GUEST: We got this picture back in the '30s.

My father was studying forestry, and he would take the young, underprivileged kids in the western part of the state all over the natural historical sites, Indian locations, and the likes.

It would be all over Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming.

So it would, they would be about two-week treks, and, uh, they'd pile everybody in the back of a pickup truck... Mm-hmm.

...and then drive 'em around and camp in each of these locations.

As a result, they gave him this picture as a gift.

It's painted by a Native American artist, and he was a Navajo artist by the name of Narciso Abeyta.

His Indian name was Ha So De.

He was born in 1918, and in 1939, he was one of the first classes at the Santa Fe Indian School to be taught by Dorothy Dunn.

When they were sent to Indian schools to anglicize them, Dorothy Dunn encouraged all the children there who were taken from their tribal lands to remember their Native ways.

And there were many famous American Indian painters from that class.

But the interesting twist in Abeyta's life was in the early '40s.

He was the code talker in the Pacific Theater.

Navajos, the code talkers that helped the Marines.

And these people were sent home, sworn to secrecy, all the Navajos, and they were not allowed to talk until it was declassified in 1968.

If you can imagine, being taken from the tranquil grounds that he grew up on and be thrown into the Pacific Theater with all the danger and the change of climate, the jungles.

Unfortunately, he was shell-shocked, and his painting suffered for it.

So you acquired a painting that was done in his prime, and it's really quite wonderful.

He and the other code talkers were, weren't recognized till 1981 for their service to this country, and Abeyta died in the late '90s.

He actually has a son, Tony Abeyta, who follows his, his father's tradition and works in the contemporary vein, too.

I'm sure this is a gift of great affection, but when they purchased this for him, they probably paid as little as $15 for it.

On today's auction market, it would fetch in the $4,000 to $6,000 range.

Wow.

But it's a great painting by a man who lived a very rich, colorful life.

He was also a Golden Gloves boxer and a silversmith.

Oh, I'm impressed.

So I'm glad to see this painting here today.

Wow.

GUEST: My parents collected jewelry from the Southwest, and these are two Charles Loloma pieces that I believe they got in the early '70s through the Heard Museum.

And we actually have the receipts, so that it was some... APPRAISER: Okay.

It was under $200.

Oh, you're kidding me.

Per piece.

These are by Charles Loloma.

He was a Hopi artist from Third Mesa, from Hote, Hotevilla, or Bacavi, and it's on the Hopi reservation in Arizona.

He was a modernist silversmith, a jeweler.

He is really the godfather...

Uh.

...of American Indian jewelry.

His influence and his impact on jewelry altogether... Mm-hmm.

...has just been unprecedented.

These are tufa-cast.

It's actually a really soft sandstone.

Mm-hmm.

Easy to carve into, and then you... (blows): ...blow out the, uh, dust.

Mm-hmm.

And you carve all of these designs into them.

In, in this case, this one being very simple, just a simple band, and it's all about the texture, and this is an abstracted landscape.

The thing that's really exciting about these two, they're early.

These evolved into very complex, large inlaid bracelets with ironwood, coral, turquoise.

They became gold, sugilite.

They got to be very beautiful.

But I backpedal to this period, which I like the best.

Very innately Hopi, and I just love that.

Now, Charles Loloma, he was born in 1921... Mm-hmm.

...and he died in 1991.

He studied at Alfred University, and he was also a instructor for a short period of time at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Do you have an idea about the, the value of these at all?

I would say for the two pieces, about $15,000.

Okay, so that would be, what, $7,500 each?

Mm-hmm.

They're signed on the back.

Correct.

They come with provenance, right?

Mm-hmm.

Receipts?

Yes, from the Heard.

Um, and they are also really... (chuckles): ...iconically by Charles Loloma.

I would venture to say that in today's market, this bracelet alone, probably, in the retail marketplace, about $25,000.

Whoa.

Can I sit down?

Only kidding-- wow.

(laughs): Yeah.

This bracelet... Wow.

...maybe a little more.

Like, why?

Because people like turquoise.

And look at that great penetration through the stone.

Yeah.

The fact that it goes all the way through, it's remarkable.

Mm-hmm.

And it's just a really great example of his m, restraint and creativity.

$28,000.

Wow.

(stammers) So, yeah.

So my parents did very well when they purchased these back in the '70s.

I mean, they're beautiful pieces.

APPRAISER: This piece is what we call a discoidal or a chunkey stone.

It was for the chunkey game.

It is Mississippian culture, which dates to 1000 to 1500 A.D.

So they really predate European contact.

They're using stone instruments and wood instruments to grind these down into form, so just think of how hard that would have been to use another stone to get this as soft and smooth.

The game was a game where they would roll the piece through a lance.

It was an accuracy kind of game.

Okay.

APPRAISER: It's a Plains Indian courting flute.

Warriors used to stand outside the teepee and court their sweethearts with this.

This is a particularly beautiful one.

There's traces of red ocher, both in the, the buffalo hide ties and on the loon itself.

It probably dates to the mid-19th century, which is quite early for something like this.

I think I'd put an estimate of about $6,000 to $8,000 on it.

Wow, that's, that's fantastic.

GUEST: This belonged to my great-great- aunt Ruth Muskrat Bronson.

She was a civil rights activist.

She was an author, a poet, a songwriter, an educator.

To me, uh, she is so special-- she was a woman before her time, and she did a lot of things for Native American people that we can all still be proud of today.

What was her era, so to speak?

She was born in 1897.

This picture was taken in 1923, when she was a junior in college at Mount Holyoke.

And this is at the White House in Washington, D.C.

Okay.

This is my Aunt Ruth, and this is President Calvin Coolidge.

And this is a book that she presented to him that day.

And she also gave a speech that day.

Is the dress that you're standing by the one she's wearing in that photograph?

This is the dress that's in the photograph, yes.

Okay.

And, and that's the same dress that's in this photograph.

Were the moccasins and the dress created for the presidential event?

That's my understanding, yes.

They were intentionally not Cherokee items... Mm-hmm.

...so that she could be representative of more than just her tribe, and be representative of all American Indians.

This is the speech that she delivered at the White House, is that right?

Yes.

And to read through that speech, it gives me goosebumps.

She said such amazing things that President Coolidge invited her to come to the White House for lunch at a later date, which she did.

In the speech, she tells who made the beadwork.

Both the moccasins and the dress were made here in Oklahoma by Cheyenne bead-workers.

The hides are brain-tanned deerskin, which were never inexpensive.

They were always, incredibly high price to get them.

They were difficult to make.

And I thought the moccasins might be Lakota because of the designs.

But then I got to looking, and there's a welt right here between the sole and the beaded uppers.

You notice that trait in lots of Cheyenne moccasins from Oklahoma, you know, the Southern Cheyennes.

Do you know what she was talking to the president for?

Well, this was the Committee of One Hundred in 1923, and I believe she was asking for civil rights for Native American people.

Right.

And also fighting for Native Americans in the laws that were be, being created at that time and talking about the "Indian Problem."

And she wanted the president to hear from an Indian what the real Indian Problem was, and it wasn't what the other people were calling the Indian Problem.

She wanted everyone to accept Native Americans as Americans and to allow them to be educated just like everyone else.

Yeah, I saw in the letter, she's asking for education for all.

Yes.

Where did she live?

She was from Grove, Oklahoma.

Oh, yeah.

She was my great-grandmother's sister, and that's where our whole family was from.

That's where our allotment land, uh, we still have that allotment land, um, but she, she lived in Washington, D.C. She worked there for the government, for the B.I.A., and then she retired in, uh, Phoenix, Arizona.

She was helping different tribes her entire life.

When she passed away, I believe she was in Arizona working for water rights for tribes out there.

Oh, yeah, that's a big deal.

Yes.

She's asking for what we consider basic human rights...

Absolutely.

...in this country today in the '20s.

And, and after that, you get the Depression, and things really got bleak.

Now people have awakened to these situations, but they didn't do it without a pushback.

And that's why a lot of rules have been passed, laws have been enacted, everything from the Native American Sovereignty acts to NAGPRA, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Acts.

And they protect this cultural patrimony that's been handed down, in your case, through your family, but also in national input.

And this was the early days of all that.

These were the people that pushed that to try to make it happen.

When you brought this dress in and the moccasins, I looked down and I said, "Yeah, nice moccasins, nice dress."

In this condition, and mainly because they're late, if you were going to see these things at auction, you'd expect 'em to bring $800 to $1,200.

But that's not what's here.

That's not what this is about.

This is about, this woman wore these things to represent a pan-culture, almost, that spread across the United States that she was fighting for, for rights for.

When you start looking at it from that point of view-- her meeting with the president, the original speech-- and I think you're talking, for all of that you have here-- and you have more, you have more archival material, more photographs-- if you were to bring these up for insurance, it gets more like $8,000 to $12,000.

Wow!

And these things are priceless to our family.

Oh, I'm sure.

So, yes.

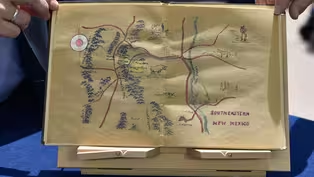

GUEST: This is a book I, I purchased online a few months ago.

Apparently, it was published by the Tesuque Pueblo Indian School back in the 1930s.

The teacher and the students put the book together.

They, uh, students drew and colored the maps.

Right.

And, um, they didn't have enough money to publish it, so they used their food money, from what I understand, for the month... Uh-huh.

...to buy a mimeograph machine.

Amazing.

And then they printed 30 copies of it to sell for a dollar apiece to pay for the machine.

Incredible-- so it's a book that was produced in 1936 by the third-grade students at the Santa Fe Indian School at the Tesuque Pueblo.

And Mabel Parsons, who is the author here, provided the text... Mm-hmm.

...with Anna Nolan Clark, who was another teacher at the school.

And their hope was, as I understand it, to help these students learn English and, uh, overcome their fear of books.

Correct.

And they came upon this tremendously interesting idea of having them make a book...

Correct.

...and use the text.

Now, as you mentioned, they, um, in the process of creating this book created mimeographed pages, including a series of ten maps, which the children themselves would hand-color using colored pencil on mimeographed paper.

They would hang the mimeographed sheets to dry out.

And what I think is so fascinating about this is, they're using their own knowledge of the geography and where they are to get them interested in reading.

These Native American schools, the Indian schools, were very controversial, are controversial, for trying to indoctrinate these children into Western ways and give up their Native American heritage.

But at least in this instance, there was some effort to approach them with a sensitivity to their geography and their place of home.

Correct.

So you have things like this map, uh, this, this, this rose compass that would be on a map, and it has a Zuni symbol on it.

It's really phenomenally interesting.

We'll look at another map in here that they created, and it has a similar layout with lots of hand illustrations by the children.

It's really a, a, an unusual object.

There was a, an article written about this book recently in, in a Santa Fe newspaper, right?

Correct.

It's an extraordinarily rare object.

You kind of stumped us a little bit, because you normally, when we try to evaluate something, have comparables, other objects similar to it, even if we don't have the same edition.

There really have been no copies of this book sold, at least at auction, in, as far back as I can see.

But even in the context of, you know, frontier literature, you might have a small printing press on the, on the frontier in Wyoming and so forth, but that would be run and managed by, obviously, Western settlers.

This is a book printed on the Tesuque Pueblo in 1936 by children in the third grade.

And I can't think of another example like it.

Yeah.

It's really an amazing thing.

Pretty amazing.

So will you please tell me possibly what you paid for the book, and possibly why you bought the book in the first place?

I paid about $300 for it.

All right.

Which, for me, was a lot to spend on a book.

Yeah.

But, uh, I, I'm an archaeologist, I like history.

Uh, my mom used to work with the pueblos heading up, uh, Head Start programs.

Oh, right!

So, uh... Amazing.

I had that, kind of a connection that just kind of spoke to me.

There has been at least one copy that might have been offered by a private dealer in recent years, but that appeared to have been incompleted.

Probably only had five maps, according to what I understand.

In a situation like this, I would say, for, uh, valuation purposes, we would want to be conservative and to see how much interest institutions and others would have in it.

But in an auction context, I would say it'd probably have an estimate of $3,000 to $5,000.

Oh, wow.

We know that nine institutions had one, leaving about 20 in private circulation.

Yeah.

When my son was five, which is longer ago than I want to admit, but about 25 years ago, um, I sent it to school with him for show and tell for kindergarten, along with another basket that I have.

Was a little careless with it.

And it wasn't until a few years later that I learned it had some value.

How did you acquire the pot?

My grandfather moved to Colorado in the late '30s, and he acquired it out there.

And I don't think anyone in the family knew anything about it, except just that we thought it was a, a pretty pot and perhaps looked nice with plants in it at one time.

Well, luckily, you didn't put plants in it.

One of the most important features on a pot like this is the fact that it's what we call black-on-black pottery.

Uh, the very shiny gunmetal design or gunmetal finish is characteristic of a type of pottery that was produced in San Ildefonso, still being produced today.

If you'd have put water in the pot or had plants in it, uh, eventually it would cause the, the finish to start to flake and peel off.

It would.

And it would have really hurt the value of the pot.

This particular pot has a signature on it, and the signature on this pot's what makes all the difference.

The signature is "Marie."

Mm-hmm.

And she also spelled her name "Maria."

But, uh, in this particular case, Marie is the way she signed it, generally in earlier periods... Oh, okay.

...than, than when she signed it as Maria later.

And this was Maria Martinez.

She was probably the most famous potter of the San Ildefonso Pueblo.

And her pottery is very highly sought-after today and very collectible.

Mm-hmm.

And luckily, your piece is in pretty good condition, considering that your kindergartener... (laughs): Considering kindergarteners, okay.

...taken it, took it to, uh, kindergarten, yes.

Um, do you have any idea what the piece is worth?

Or have you had it...

I have guessed maybe $1,000, but I have no idea, really.

Well, this size pot, by, perhaps, a lesser-known artist, would be in that range.

However, with Maria's work, you could expect to probably triple that.

This pot should be worth about $3,000 today on the market.

That's nice.

(laughs) GUEST: It was a drawing by Ernest Spybuck.

APPRAISER: Spybuck was an Absentee Shawnee Indian.

I believe this was painted in 1910, 1920.

This depicts the grass dance.

What's wonderful about this is the high level of detail.

We feel that in a retail setting, about $4,000.

That's nice.

GUEST: I've inherited it from my great-grandmother.

It is a lei niho palaoa from Hawaii.

It's made of braided human hair and whale bone.

They were generally made out of a sperm whale tooth.

Now, the sperm whales would just be washed up.

And that was a pretty rare occurrence.

So anything wonderful like that would only go to the royalty.

This one is a walrus tusk.

You've done a wonderful thing by putting it in a frame, and it really is an icon of Pacific art.

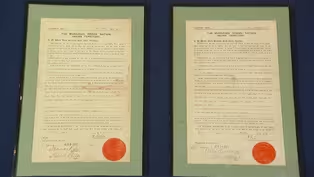

GUEST: I'm a member of the Muscogee Nation, and these are the original documents from my grandmother and grandfather on my father's side of their allotted land for Indian Territory.

Each received 160 acres.

This is on the Verdigris River, uh, between Wagoner and Coweta.

APPRAISER: Not too far from here.

Not too far, about 30 minutes.

Right.

We still own my grandmother's allotted land.

It's in our family still, with the original house still on it.

At the time, every citizen that was on the Dawes Rolls was able to get 160 acres per person.

My grandfather and grandmother and their eldest living child, she received at the age of two.

But I only have the documents from my grandmother and grandfather.

And why are there different dates, 1905 and 1903?

Well, they were consecutive in their roll numbers-- that's their roll numbers for our tribe.

Right.

And down here is when they were signed by Pleasant Porter, our chief at that time, and then at the Bureau of Indian Affairs, gave the allotments to my grandparents.

We've seen others of these today, but never a consecutive number.

They're both in very good condition, with the exception that the 1921 document suffered some water damage.

But, uh, I see you've had them nicely preserved, you said in a book?

They were found in a book, yes.

And, uh, that's helped them extremely.

My colleagues and I both thought that you should probably have an insurance value of around $500 on each of them.

Wow!

Because...

Thank you very much for bringing it along to us.

Thank you!

You brought us this great letter dated July 20, 1933, from one of the greatest athletes of all time, the legendary Jim Thorpe.

1933-- I'm assuming he didn't send it to you, so how did you get it?

(laughs) (laughing) We do have good genes in the family, but not that good.

My grandparents lived next door to Jim Thorpe in Hawthorne, California.

It was pretty much agricultural area there, and they raised dogs, and my grandfather took care of Jim Thorpe's dogs when Jim was out touring, whatever he did in those years.

He wrote back quite a few letters to see how the dogs were doing.

He was always, uh, playing tricks on the kids.

My mom tells a story.

He came outside and asked 'em if they wanted some chocolate, and gave 'em a handful of chocolate, and they ate it, and he was just laughing uproariously, and said that it was, uh, chocolate Ex-Lax.

(both laugh) So... (shudders) Maybe you don't want to eat dinner over there, I guess!

So what did you find fascinating about this particular letter?

Well, I like that his dog was named Geronimo.

(laughs): That's right.

I mean, it's perfect.

We see right here.

He asks, "I'm glad to know that all "the dogs are going good-- how is Jeronomo doing?

Can he still run, or has the old hurt bothered him?"

But he also mentions here that he's being owed money.

Yes, yes.

And he's waiting for that.

To get paid.

My mom did say that it seemed like when she was growing up that they did live hand to mouth.

And that to me is what gives this letter its poignancy, is that here you have Jim Thorpe, who in 1912 won the Olympic decathlon and the Olympic pentathlon and was called by King Gustav V at the time, "You are the greatest athlete in the world."

And Thorpe went on to play professional football, professional baseball, was known as one of the greatest football players of all time, was inducted into the first football class of a hall of fame.

I didn't know that.

But what, unfortunately, what has happened, and it's happened to athletes and entertainers over the years, that just because they are the greatest at what they do doesn't mean that A, they aren't human, and B, they don't fall on hard times.

This is dated in 1933-- this is the heart of the Depression.

Pression.

And in the '30s, he was scrambling.

He was an American Indian, half of his heritage, and he had to face an enormous amount of discrimination.

In the '30s, he played bit parts in over 60 movies.

Wow.

And over half of them, he would play a stereotypical American Indian.

Indian.

But he did what he had to do to make money and occasionally, he would also coach, which is where we think this money came, and we're not sure.

It says here, "If only I get it.

"I have $1,250 coming now in this year.

But it seems rather hard to get it from the owner."

Owner.

And I mean, he faced what a lot of folks did in the Depression.

And you see this last page is also slightly heartbreaking.

"Mrs. Thorpe has not written me very much."

They did not have a great marriage and ended up getting divorced.

"Wish you would write and tell me what's going on.

"Are the boys in good health?

"How's your family?

"Have sent money to Mrs. Thorpe now and then, but was up against it for a while."

Yeah.

The great thing about Thorpe, you see in this letter, things may not have been great, but he still was fighting as hard as he could.

And it sounds like he's very optimistic, even.

Exactly.

One of the saddest things about Jim Thorpe is that he won the Olympic medals in 1912, but he had played baseball briefly for money, because he had no money in the early 1910s, teens, and the Olympic Committee took away his medals.

They basically stripped him of his medals.

And he did spend a good chunk of his life trying to get those medals back.

When he passed away in 1953, they had still not given them to him.

And 30 years later, they reinstated his medals to him.

Because of Jim Thorpe's stature as a great athlete, both in the Olympics and a professional athlete-- and you also have the envelope here, and this is a six-page handwritten letter-- I would say, if you were putting this out at auction, that it would sell for probably in the range of $5,000.

Oh, wow.

And if I were going to insure it, I'd insure it for $10,000.

(gasps): Wow, cool.

GUEST: During World War II, my father-in-law was stationed in the Aleutian Islands.

And one day, he was walking along the beach and saw this and picked it up.

After the war, he took it into the San Diego Museum of Man and loaned it to them.

I guess he expected them to put it on display with his name on it.

They didn't.

That irritated him.

So he went back and took it back and then gave it to my wife.

Well, so now that was in, what, the late '40s?

I am guessing late '40s, early '50s.

All right.

We've had it as long as we've been married, 40-plus years.

Great.

All I know is, it's gorgeous.

Let's first of all talk about geography.

Now, the Aleutian Islands extend from Alaska west towards Russia.

You sometimes hear it pronounced, the people, pronounced "A-loot" or "A-lyoo-eet."

Yes.

I want you to think back to all of your "National Geographics" specials where you saw seals.

Hm.

And I want you to imagine that the top here is the ocean.

This is exactly what you see of the seal's head as the head is coming up out of the water.

I think that's not an accident.

Now, I want to look at the backside.

The first thing you want to say is, "Okay, w, how is this used?

Does it make sense?

Could this thing be authentic?"

Initially, you think this might be a mortar of some sort.

But then you see this dark area.

And I think almost certainly this was an oil lamp.

They would have burned seal oil, whale oil, or walrus or something like that.

And there would have been a wick that extended out.

So... (groans) I think that we can say pretty clearly that this piece is authentic.

Understand that the seal is very, very important to the sustenance, the survival of these people in that part of the world.

It's really tough, tough conditions.

So the spirit of these various animals that they depended on were revered, and they paid homage to 'em.

And that's why we see these forms occurring in the various art.

So this makes sense.

Something like this is extremely rare.

That's what I was afraid of.

Extremely rare.

So how old do you think it is?

I'm guessing...

Hundreds, possibly thousands of years old.

Okay, we really don't know.

But we do know it's pre-contact.

Oh, God.

And pre-contact means that it could be anything...

It could be thousands of years old.

We just don't know.

We know it's authentic.

We know that it's early.

We know that it's rare.

What sort of value do you think?

I would be al, afraid to guess.

The consensus on the table was $4,000 to $6,000.

(breathes deeply) Now, four, that's $4,000 to $6,000.

Yes.

And that would be in a gallery or at auction.

Right.

Now, we did have some people that felt that it was as high as $5,000 to $7,000.

Now, having said all of that, we do have something that we have to consider.

The Aleuts have been very, very aggressive in trying to repatriate objects that they consider to be sacred.

If it came off federal lands, it would certainly be something that somebody couldn't just pick up.

So, there are issues that need to be studied with respect to this piece.

And we have to respect the patrimony of the people that, that live there.

Absolutely.

So that is a big concern.

It's a very, very special object.

GUEST: I brought a wooden bowl that has been in my family for many years.

It had been passed down from mother to daughter, all sharing the common name Mariah.

That's my middle name.

So that's why I got the bowl.

It is a wooden bowl.

Mm-hmm.

And it's actually a burl wooden bowl.

Oh, okay.

And burl is harvested from an outgrowth on the tree.

It's cut off and then carved.

And it usually has a, a most interesting pattern because it is an outgrowth.

And in this case, the wood is ash.

Oh, okay, I never knew.

So we would actually call it an ash burl bowl.

Oh, okay.

We do agree that it really dates back very early, probably to the early 1800s.

Mm-hmm.

And could even be late 18th century.

We see the wonderful pattern that Mother Nature has formed.

We also see a foot.

Right.

And the foot... We feel that the entire conception is made by a Native American.

I had a great-great-great-grandmother who was half-Native American from a Indian tribe in Western New York, but nobody knows what tribe.

And she was born in the late 1700s.

Okay, so we're starting to... Oh!

Yes.

...connect the dots here.

Oh, my goodness.

We don't know the exact tribe, but we refer to it as "Woodlands."

So it could be as far west as Iowa... Mm-hmm.

...where, obviously, your family ended up, and possibly was brought there by other family members.

Right.

Yet the Woodlands go right to the Atlantic Ocean back east, so it covers a pretty wide range.

Right.

And this foot, we feel, was influenced, possibly, by a piece of early Colonial treenware that one of the Native Americans might have seen.

And they put this foot on the bowl, which is a wonderful additional element, as well as this crease line...

Right.

...which adds an element of design and a sense of style to it.

Now, when we turn it, what we see, you would call this a handle.

Right.

And really what it is, it's an abstraction of a spirit being.

And the spirit being they called a "manitou."

And this is actually the arms and the head and the other arm.

So it's actually a human form.

It's a...

It's a, a form.

It's not an animal form.

Oh, my goodness.

I knew there was something special about the bowl, but I thought it was because it was a family item.

It just has all the elements in it that clearly indicate Native American-made.

I would say, retail value, in today's market, I'm gonna be conservative and say $12,000 to $15,000.

Oh, my goodness.

Really?

It was just a utilitarian item on the farm for hundreds of years.

Oh, my goodness.

GUEST: I saw it at an antique store in Paradise, California.

The tag said it was a tea cozy, but it's pretty big.

It's a tea cozy, and it fit over a big teapot.

The, the biggest one I've ever seen.

This is from the eastern side of the Great Lakes, probably made between 1880 and 1910.

This has got to be the most spectacular piece of, of beadwork from the Great Lakes I have ever seen in my life.

It was my father's.

This was in the mid-1950s.

He was a judge, a circuit court judge, and he was asked by the Seminole tribe to come to the reservation to hold a trial.

So they wanted him to wear this in his tribal judgments.

Right.

That's great.

It was a very special gift.

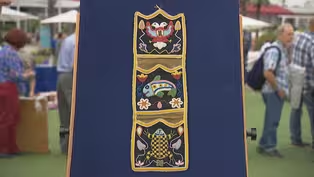

GUEST: It was given to me by our, a neighbor friend, because we went garage sale-ing every Saturday morning, and she went by her neighbors', and she found it in the trash of her neighbors.

I assume it's Northwest Coast because of the killer whale.

And that is really all I know.

It is from the Northwest Coast, and it was made by a member f, of the Tlingit tribe, a woman.

And it's got two very significant clan symbols, the frog and the killer whale, the orca.

The one on the top is the double-headed eagle of the Russian Empire.

Now, there is a history of Russian Orthodoxy in this part of the world.

And I'm not sure whether she was part of that or not, or just used it because it was a rather nice symbol.

And you have this sort of vegetation, this foliation around the outside.

And it's got really nice old calico on the inside.

It's a wall pocket, and would have been made probably not for tribal use, but for sale, um, as a tourist item.

It was made about 1880.

Really?

So it's quite early, but the condition is really beautiful.

Oh, yes.

And the beadwork is just lovely on it.

I think a retail value would be $2,500 to $3,000.

Ooh!

Marvelous!

And if you wanted to insure that, I'd insure it for probably about $4,000, $4,500.

Thank you.

Wonderful.

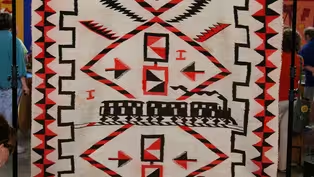

In the very early '60s, my grandfather had passed away, and my father made me and some of the other family members go to his house to clean the basement out.

And this, along with a lot of other, we thought, junk was just laying on the floor in the basement.

And it was gonna be thrown away.

And I, being 12, 13 years old, I dragged it home.

And I think it's a Navajo rug.

Later years, I learned that my grandfather and his brother, they were both architects.

And they worked for different mapping companies, and they dealt with railroads, and I'm sure that's where it came from.

What you have here is indeed a Navajo weaving.

After the Navajo were weaving garments for their own personal use, and before the actual rug period started, in about 1905 or so, there was a, a period of about 20 or so years of transitional weaving.

The yarns are homespun yarns.

The dark brown is natural yarn color, and the cream is a natural yarn color.

Right.

All the red within the weaving is actually a commercial synthetic dye...

Okay.

...which they used commonly in that timeframe.

It was woven on an upright loom, and it's very pictorial.

One of the best icons of the American West is pictured right in the center of your weaving, the steam locomotive.

You see the barber pole striping right here used for the train tracks, as well as for these design elements right here, are taken from early Navajo wearing blanket designs.

This weaving is from the Crystal area on the Navajo reservation, which is on the western edge of the state of New Mexico.

This weaving dates to about 1890.

You have some spotting going on here.

You have some red dye that has bled into the weaving.

Because of the condition, this particular textile would probably realize a value at auction between $8,000 and $10,000.

Eight and ten?

Yes.

If the weaving were to be successfully restored, this weaving could probably realize a value more of $12,000 to $15,000...

Okay.

...on today's market.

Okay.

GUEST: My great-aunt, Savannah Beck, went to Carlisle Indian School in the early 1900s.

She and two of her brothers and a sister and a cousin all attended the school.

As far as I know, she's the only one that graduated, with a degree in practical nursing.

My mother inherited them from Savannah's daughter.

And you know the Carlisle Indian Industrial School was founded around 1879.

Right.

And it was basically the first off-reservation boarding school for the Indian kids.

And what you brought here is phenomenal.

I know it's just a small portion of an enormous archive that you have.

The key to this whole setup that we put together, as far as I'm concerned, is, you have her diploma.

Right.

And we have a wonderful booklet here, which is the commencement exercises for 1909.

And all of the printing of these booklets was done...

Right.

...right there at the school.

Right, all of the students did the printing for all of the events on the campus.

What we have in front of us in these two pictures is an absolute who's who of football history.

This is a 1903 team photo from the Carlisle team.

Right, mm-hmm.

Over here on this side, that's a picture of probably the most famous football coach in football history.

That's Pop Warner.

Right.

And he coached that team.

And over here on this side, you have a picture of Art Sheldon...

Right.

...one of the most famous people in football history, known for the hidden ball trick.

Exactly.

And a photo like this is just incredible.

To top that off, you have a photo here of probably the most famous person ever went to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School.

Right.

It's Jim Thorpe.

Jim Thorpe was probably one of the greatest, not just football players, but athletes in American history.

What's wonderful about this is, it's a phenomenal photo of him.

And to add even more to it, on the back, Jim signed this in 1912.

And that's to Savannah Beck.

Savannah Beck.

Yes.

That's your aunt.

All-American, half-back, 1911.

It's absolutely incredible-- this is a photograph at an early stage of his career...

Right.

...autographed by him.

This is something you just never, ever see.

When you try to give an estimate on something like this, it, it's virtually impossible to be real accurate with the quantity of material you have, because every piece has a value.

Exactly, yeah.

And every piece has an historic value.

Easily, I would estimate this, as an archive, at auction, with these two pieces obviously being the centerpiece of that collection, at $15,000 to $25,000, at least.

And I think I'm being quite conservative when I do that, because a Jim Thorpe piece like this could sell for $5,000 to $10,000 by itself.

Rare, rare stuff.

And amazing that it's been kept together for this length of time, I mean, it's just it...

I'm astounded, and I'm really thrilled that you brought it to the "Roadshow" today.

Thank you.

My mom worked with a lovely little lady who became ill. My mom and dad helped her out a little bit.

And when she passed, she had left a note for her landlord to call my mom if anything happened to her.

And the landlord called us, and we were sad she passed away, but he wanted everything out of her house that day.

(chuckling): My husband and I took the day off work, and we went down with his big truck and started loading all of her furniture.

And one of the last places we looked was up in her bedroom closet.

And there was a big hat box sitting up there.

And my mom said, "Oh, in the '40s, "she was a wonderful fashionista.

I bet there's a beautiful hat."

So we got all excited, and I brought it down and opened it up, and this basket was in there.

And that was July of '88.

So 30-odd years I've had it.

And I think she got it maybe from the Indian Days that they used to have at Yosemite.

There was either three or four ladies that made baskets for those occasions for tourists.

And I think that, it's a different design, but it looks like the one that they have online for, her name was Carrie Bethel.

I would totally agree with you that it is a Carrie Bethel.

Oh, cool.

This woman was so consistent in her materials that everything had to be just so.

Oh!

Oh!

Everything w, and that is why this basket is so beautifully woven.

This design right here is very reminiscent of a medallion.

And then she repeats that design.

No stitch is out of place.

And I would say that she wove it between 1955 and 1960.

She lived in the Yosemite National Park area.

This woman, who was such an unbelievable weaver, lived in a shack.

She had no running water.

Oh, my gosh.

No electricity.

What?

And she just did her weaving when she could during the day, because she had to make money.

She was a domestic.

The highest price that she got for a basket was $180, and that was maybe for two to four years of work.

Wow, wow.

This basket took at least two years to make.

Jeez.

And you remember, she wasn't weaving at night because she couldn't see.

Right, she was work... Oh, yes, right.

The background material is sedge.

Sedge.

Bracken fern, the black.

Oh.

And inside each one of those rows are three rods of willow.

And the red is redbud.

When someone weaves a basket, and then they might want to weave another one, maybe the exact same, it's never gonna be the exact same.

Oh, so they're all different.

Right.

They're all different.

They wanted to weave different kinds of design... Sure, sure.

...because most of their work, it was done for sale.

Right.

And when, especially with Carrie... For tourists, kind of like.

Yes.

Yes, for tourists, exactly.

Ah.

And they put out their very best work.

Now, after the '60s, they started getting smaller, the baskets.

Oh.

Because they c...

Tourists wanted something they could carry home.

Carry wi... One of her baskets sold in 2006 for over $200,000.

Oh, no.

Oh, yes.

You're kidding!

Her work... She was a master weaver.

There were a lot of basket weavers, but Carrie was one of the major ones.

Oh, my gosh!

This is one that one would say, "Oh, this is a Picasso"... Oh!

Oh, my... ...if you're talking an... Oh, and now I feel horrible.

...artist's work.

(chuckling): It's a decoration in my house.

Unders...

Yes, it's a decoration, but you also put plants in it and stuff.

I did.

Which is a no-no.

(laughs) I would put a price on this basket at auction of a good $75,000 to $85,000.

Oh...

Yes.

Now... What?

You heard me right.

Oh, my gosh!

You heard me right.

Oh, now I do feel bad.

Ooh!

Now, I don't know what it would cost to repair.

I would personally pay five grand, because then you could possibly sell it for maybe way over $100,000.

Whoa!

Oh, my gosh!

Now, are there any other things you would like to know?

(exclaims): No, I'm freaking out now.

Gosh, I mean, I just love it.

I love all Native American stuff, and I just feel really privileged to ever even have it.

I would insure the basket probably for $150,000.

(exclaims) (grunts) I just... (exclaims): I can't breathe.

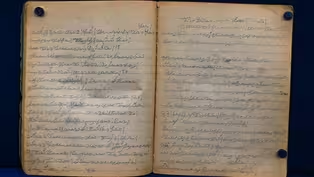

GUEST: This book is about the first Yup'ik writing.

And this was written by my grandfather.

And he learned to read and write this, um, written Yup'ik language from Uyaquq.

And he was known as Helper Neck.

I think this is an amazing book.

As you were saying, Uyaquq means "neck" in Yup'ik.

In Yup'ik, yeah.

And basically Uyaquq was a helper in the Moravian Church, which, hence the name Helper Neck.

Quite fascinating that he did this in five years and then started teaching it to others.

Mm-hmm.

Can you tell me a little bit more about your grandfather, and how long maybe it took him to even learn how to do this himself?

Um, both my grandparents learned to read and write like this.

I grew up living with my grandmother as a little girl.

And she would read and write that.

That was the only way she could read and write.

But I didn't pay attention at the time.

But then...

So you never learned yourself?

No.

I don't know of anybody that can read and write Helper Neck's writing today.

And my grandparents did not speak English.

They only spoke Yup'ik.

And I couldn't read that, so, um, but I've got his manuscript.

And I've also got my grandmother's manuscripts.

And do you know if there's any of these anywhere else, maybe?

I heard that there was two other manuscripts, or books, I called them, but they were at, uh, museums.

And my grandfather went to villages and taught other people the writing, and they always called it Uyaquq, Uyaqum igai, which means "Helper Neck's writing."

And what does this mean to you?

I grew up watching that.

Not my grandfather's writing, but my grandmother's.

So they mean a lot to me, just because of the history.

So one of the things that I think is very important about this piece is, as we've known through Alaska Native cultures and the languages, that they have been dying off for a very long time.

Some of them are almost extinct.

And so it's really wonderful to be able to see and have this written Yup'ik language and being something that is a strong example of carrying on the Yup'ik language and culture, and making sure that it's preserved for future generations.

I think it's very precious and obviously priceless for you and your family.

I would probably s, insure a book like this for maybe over $100,000.

But I also think that it's so unique in its nature that it would take some more research with other people to find out a little bit more about it.

And maybe the price and value could go up.

Yes.

But it's a treasure.

Mm-hmm, yes, it is-- thank you.

Mahsi'choo.

Mm-hmm, quyana.

You are somebody that speaks Yup'ik yourself.

This is something that you could be very proud of.

Yes.

PEÑA: Thanks for watching this special episode of "Antiques Roadshow."

Follow @RoadshowPBS and watch us anytime at pbs.org/antiques or on the PBS app.

See you next time on "Antiques Roadshow."

Appraisal: Narciso Abeyta (Ha So De) Painting, ca. 1935

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S28 Ep23 | 2m 41s | Appraisal: Narciso Abeyta (Ha So De) Painting, ca. 1935 (2m 41s)

Appraisal: Seminole Circuit Court Judge's Robe, ca. 1955

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S28 Ep23 | 23s | Appraisal: Seminole Circuit Court Judge's Robe, ca. 1955 (23s)

Appraisal: Mississippian Granite Discoidal, ca. 1000 - 1500

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S28 Ep23 | 1m 47s | Appraisal: Mississippian Granite Discoidal, ca. 1000 - 1500 (1m 47s)

Appraisal: 1970 Charles Loloma Sterling Silver Bracelets

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S28 Ep23 | 3m | Appraisal: Charles Loloma Sterling Silver Bracelets, ca. 1970 (3m)

Appraisal: Yup'ik Language Manuscript, ca. 1895

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S28 Ep23 | 3m 19s | Appraisal: Yup'ik Language Manuscript, ca. 1895 (3m 19s)

Appraisal: Carrie Bethel Basket, ca. 1958

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S28 Ep23 | 5m 1s | Appraisal: Carrie Bethel Basket, ca. 1958 (5m 1s)

Appraisal: Plains Indian Courting Flute, ca. 1870

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S28 Ep23 | 1m 44s | Appraisal: Plains Indian Courting Flute, ca. 1870 (1m 44s)

Appraisal: Ruth Muskrat Bronson Archive, ca. 1923

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S28 Ep23 | 4m 58s | Appraisal: Ruth Muskrat Bronson Archive, ca. 1923 (4m 58s)

Appraisal: Navajo Transitional Pictorial Weaving, ca. 1890

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S28 Ep23 | 2m 29s | Appraisal: Navajo Transitional Pictorial Weaving, ca. 1890 (2m 29s)

Appraisal: 'A Courier in New Mexico' book 1936

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S28 Ep23 | 3m 37s | Appraisal: 'A Courier in New Mexico' Book, ca. 1936 (3m 37s)

Appraisal: 1903 & 1905 Muskogee Creek Nation Allotment Deeds

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S28 Ep23 | 1m 56s | Appraisal: 1903 & 1905 Muskogee Creek Nation Allotment Deeds (1m 56s)

Appraisal: Tlingit Wall Pocket, ca. 1880

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S28 Ep23 | 1m 22s | Appraisal: Tlingit Wall Pocket, ca. 1880 (1m 22s)

Appraisal: Sioux Beaded Vest, ca. 1876

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S28 Ep23 | 3m 28s | Appraisal: Sioux Beaded Vest, ca. 1876 (3m 28s)

Appraisal: Ernest Spybuck Painting, ca. 1915

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S28 Ep23 | 25s | Appraisal: Ernest Spybuck Painting, ca. 1915 (25s)

Appraisal: 1933 Jim Thorpe Handwritten Letter

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S28 Ep23 | 4m 35s | Appraisal: 1933 Jim Thorpe Handwritten Letter (4m 35s)

Appraisal: Mission Indian Basket, ca. 1920

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S28 Ep23 | 1m 3s | Appraisal: Mission Indian Basket, ca. 1920 (1m 3s)

Appraisal: Woodlands Carved Ash Burl Bowl, ca. 1800

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S28 Ep23 | 3m 21s | Appraisal: Woodlands Carved Ash Burl Bowl, ca. 1800 (3m 21s)

Appraisal: Aleut Stone Oil Lamp

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S28 Ep23 | 3m 53s | Appraisal: Aleut Unungan Stone Oil Lamp (3m 53s)

Appraisal: Hopi Pottery Seed Jar, ca. 1908

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S28 Ep23 | 33s | Appraisal: Hopi Pottery Seed Jar, ca. 1908 (33s)

Appraisal: Maria Martinez Pot, ca. 1925

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S28 Ep23 | 2m 11s | Appraisal: Maria Martinez Pot, ca. 1925 (2m 11s)

Appraisal: Carlisle Indian School Archive, ca. 1910

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S28 Ep23 | 2m 46s | Appraisal: Carlisle Indian School Archive, ca. 1910 (2m 46s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Home and How To

Hit the road in a classic car for a tour through Great Britain with two antiques experts.

Support for PBS provided by:

Funding for ANTIQUES ROADSHOW is provided by Ancestry and American Cruise Lines. Additional funding is provided by public television viewers.